July 26, 2024 – In 2020, Makenna Myler’s husband posted a video of her running a 5:25 mile to TikTok.

She was 9 months pregnant.

The video went viral with more than 6 million views. ESPN posted it to Instagram. Then they took it down.

“It was controversial,” said Myler, an amateur runner at the time. “We’re still very much in a zone of fear around pregnancy.”

Throughout her first pregnancy, Myler gained insights from inspirational mothers who ran before her – Gwen Jorgensen, Paula Radcliffe, and others. She trained as she saw fit, but with little guidance, she wondered if she’d truly be able to run as she wanted to and be a mom.

After all, she had the Olympics in her sights.

Redefining Exercise During and After Pregnancy

Myler, who finished seventh in the women’s Olympic trials marathon in February, 10 months after giving birth to baby number two, is just one in a field of runners who are mothers who competed for a chance to go to the Paris Olympic Games.

Myler didn’t make the team, but some fellow moms did.

At the track and field qualifiers in June, Elle Purrier St. Pierre, who gave birth to a son early last year, finished first in the 5,000-meter run and third in the 1,500-meter, securing two Team USA spots (though she said she would run only the 1,500).

And Marisa Howard, who gave birth to a son in mid-2022, finished third in the 3,000-meter steeplechase, qualifying for Paris with a personal best time of 9:07.14.

These women trained well into their pregnancies and emerged postpartum stronger and faster than before.

“I'm part of that generation where we're really doing it,” said Howard, who credits Olympic moms Alysia Montaño, Allyson Felix, and Kara Goucher, among others, for paving the way. “Ten years ago, it was uncommon to have a baby in the middle of your career. And now I think it's being celebrated and championed.”

Times have indeed changed.

What We Know – and What’s Outdated

Today, medical professionals and major organizations such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recognize that exercise is safe in pregnancy and has many benefits, including better heart health, muscle strength, endurance, and potentially flexibility, said Alexandra E. Monaco, MD, an OB/GYN and clinical assistant professor at the University of Florida. She serves with the National Medical Center for Team USA for the Paris Olympics.

People who exercise through pregnancy generally avoid excessive weight gain, have fewer issues with the muscles of the pelvic floor, have a lower risk of birth by cesarean section (C-section), and have a lower risk of both high blood pressure disorders of pregnancy and gestational diabetes. All of this can help the mom and the fetus, Monaco said.

Exercise during and after pregnancy has also been linked with improved mental health and a possible lower risk of perinatal mental health conditions such as postpartum depression, said Miho Tanaka, MD, PhD, director of the Mass General Brigham Women’s Sports Medicine Program.

Yet, despite these benefits, guidelines about exercise and pregnancy – and postpartum exercise, for that matter – aren’t always clear.

Today, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity every week during pregnancy, but one of the hardest questions to answer remains: What are the upper limits?

Sometimes, athletes like Myler and Howard test that.

It’s important to do, considering throughout history, there’s been apprehension around what would happen to women’s bodies if they were pushed hard, said Celeste Goodson, owner of ReCORE Fitness in Franklin, TN, a certified medical exercise specialist and USATF Level 1 track coach who specializes in pregnancy and postpartum exercise.

After all, as recently as the early 1900s, maternal bedrest – not exercise – was a standard of care, particularly at the end of pregnancy, and it wasn’t until 1985 that American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists published the first exercise guidelines for pregnancy.

While promoting the benefits of exercise, those guidelines also included now outdated limits, such as keeping your heart rate under 140 beats per minute during exercise and exercising only up to 15 minutes at a time.

Goodson said outdated limits such as these were born largely out of fear. When robust research doesn’t exist, as it historically hasn’t for exercise in pregnancy, people often do what they feel OK doing.

What These Athletes Are Teaching Us

“I think I cracked open the door about the visibility of what it looks like to see a body that can move in pregnancy,” said Olympian Alysia Montaño, who famously competed at the USA Track and Field Championships in 2014 while 8 months pregnant – and again 5 months pregnant with her second child in 2017. “Your body is your body. You know what you can and can't do,” said Montaño, now a mother of three.

Rachel Smith, an elite runner with HOKA, an athletic shoe and apparel company, who was able to train through week 37 of her pregnancy, said she approached training throughout pregnancy “very open-minded” and was flexible with what her body needed.

If first-trimester fatigue stole her day, she didn’t push herself. On days she felt great, she challenged herself to do more intense runs. She returned to running after the birth of her daughter last year and finished ninth in the women’s 5,000 meters, a few spots shy of qualifying for Paris.

Howard, who is supported by Tracksmith, another shoe and apparel company, ran 35 to 40 miles a week during her pregnancy before scaling back to walk-jogs at week 25. Around 30 weeks, she stopped running altogether, switching to uphill power walking, hiking, biking, and swimming. She continued lifting as well.

When a video of her doing trap bar deadlifts and other strength moves at 38 weeks drew pushback on Instagram, she shrugged it off. “It was just, ‘Should you be exercising at this point?’ ‘What about your baby’s health?’” Howard recalled. “Ultimately, it’s my body and my baby, and I’m not going to risk my baby’s health. I felt very comfortable with everything we were doing.”

Throughout her first pregnancy, Myler also realized what her body was capable of.

“Running just became more and more normal for me,” she said. “As I progressed, I could still hit [certain] paces, and my body felt strong.”

Seven months after giving birth in 2020, Myler came in 14th at the Olympic qualifiers, and though she didn’t qualify, she signed a contract with shoemaker ASICS. She continued to run throughout her second pregnancy and postpartum experience, too. She even repeated the 9-month mile challenge with her second pregnancy, posting a 5:17 time.

Centering Women in Further Research

Stories like these push the envelope on what’s possible for pregnant bodies – and push for more research, which is crucial.

“Women have never been at the forefront of the data set,” said Montaño. “Putting women at the forefront of research in a way that gives credibility to their voice [matters because] that's what research is, right? It's expanding your dataset and hearing from nuanced, different individuals.”

The growing presence of women’s sports medicine programs and the combined efforts of various experts to support female athletes' health holistically has also resulted in more collaborative research, said Tanaka, which begins to address important clinical gaps.

In the past year or so, emerging research has suggested that it's OK to exercise hard in pregnancy. One small study that monitored crucial health parameters of pregnant women – such as maternal heart rate, blood pressure, fetal heart rate, and umbilical blood flow – during 10 intense 1-minute bouts of work found that all women reached 87% to 105% of their maximum heart rate without any adverse effects.

Of course, there’s a middle ground to be found.

“Our profession swung from, ‘you can't do anything,’ to ‘you can do whatever you want to do,’” said Jessica Dorrington, a physical therapist and certified strength and conditioning specialist, who is director of Therapeutic Associates Bethany Physical Therapy in Portland, OR, and co-founder of 4Two. “[In my experience], both Olympic and recreational athletes tend to be most successful when settling in the middle.”

The middle is often found by listening to your body. Montaño, Howard, Myler, and Smith all say this was key in their journeys – and brought them joy.

Montaño, for one, remembers slowing down toward the end of her first pregnancy and going to the track to meet up with friends and fellow athletes anyway.

“I wanted to be in my element in a way that felt really good for my soul,” she said.

Her workouts looked different than those of her fellow athletes but felt right for her body and mind.

Advocacy Helps Everyone

For women to exercise confidently and effectively throughout pregnancy and postpartum, many changes will be needed, from increased all-around support to a commitment to education and research.

When it comes to support, Montaño is also the founder of &Mother, a nonprofit that provides resources, from information about pumping and shipping breastmilk to sample contracts for sponsors – who historically dropped runners when they became pregnant, a sexist and dangerous precedent – and grants for athletes who are moms. (Montaño publicly called out Nike in 2019, prompting new maternity policies for sponsored athletes at Nike and other athletic apparel companies.)

Fellow athlete-mom advocate Allyson Felix, the most decorated track and field athlete of all time and a mother of two, has partnered with Pampers to create the first-ever nursery in the Olympic Village. The nursery will provide a space for athlete parents to spend time with their babies and young children during the Paris Games.

What All Pregnant Women Need to Know Today

Education about how the female body changes throughout the reproductive cycle matters. Without it, fear leads.

For example, if you know that you’re having something like round ligament pain (a common discomfort as the ligaments around the uterus stretch) or that your body is pumping 40% more blood than usual, you can better understand the symptoms and adjust your day or training accordingly.

“Learn the words to the thing instead of being afraid of your body,” Montaño said.

As for getting onto the road yourself? These nine pointers – vetted by professional athletes and medical professionals alike – will help.

- Know your baseline

Always check in with your own health care provider before exercising during pregnancy. Still, exercise is generally safe for both those who have exercised before pregnancy and those who have not, Monaco said. Start or continue exercise near what you did before – whether walking around the block or running sub-6-minute miles.

Also, remember that carrying a baby is exercise – your blood volume, lung volume, and cardiac output all change.

“Being a construction zone for 9 months making a little amazing human actually benefits our system,” said Dorrington. “That's a huge thing for people to realize.”

- Find an exercise you love

That could be dancing with your 3-year-old, jogging with your partner, or doing the elliptical. If running no longer suits you, that’s fine. Montaño said she often turned to a rowing machine and did walk-runs when tired.

“It's really about finding the thing that you can stay consistent with during those 9 months because consistency is key,” Dorrington said.

- Become a pelvic floor pro

During running, impact forces from the ground can increase two to three times your body weight, but there's really no research suggesting that running harms your pelvic floor during pregnancy, Goodson said.

“Much like if you're running and you're not having any knee problems, you don't need to worry about causing knee problems, if you're running pregnant and not having any pelvic floor problems, you don't need to worry about causing pelvic floor problems,” she said.

In fact, both high- and low-impact exercise can improve pelvic floor muscle function during pregnancy. Pelvic floor training during pregnancy can also prevent and treat urinary incontinence, and running technically trains your pelvic floor.

“Other factors – genetics, different levels of hormones, how the baby is positioned, muscle fatigue without proper recovery, or extra fluid or pressure – can influence pelvic floor function,” Goodson said.

If you notice any leaking, pain, or pressure in pregnancy or postpartum, dial back your training and connect with a pelvic floor physical therapist, who can help you work on strengthening, relaxing, and coordinating your pelvic floor muscles.

Some research suggests that while you can see a 17% improvement doing these exercises independently, you can see an 80% improvement when supervised by a pelvic floor PT. Ask your doctor for a referral to a pelvic floor physical therapist. Or find one via the Academy of the American Physical Therapy Association.

- Embrace flexibility

In 2022, during her second pregnancy, Myler hired elite runner and coach Ryan Hall, who helped her have both pride and patience through bumps in her training.

“Pregnancy really taught me to let effort dictate my paces,” Myler said. If something wasn’t clicking, she accepted it.

“To get better, we tend to think linearly – just a straight line of getting better and better,” she said. “But to breed success, we need to think circularly. You have to step back [to] move forward.”

Montaño said that at points in her pregnancy, she started feeling really winded at 21 minutes, so she made 20-minute workouts.

For Howard, the goal was “just to keep moving” and return to running postpartum injury-free. When her body told her to slow down – with sciatic pain or Braxton Hicks contractions (tightening of the abdomen) – she did.

“I was ready to give up [running] at any point,” she said. “Having that mindset was good for me because, when it was taken, I thought, OK, I can’t run, but I can go out and walk and hike and still get out in nature.”

- Take a holistic approach

Myler embraces a “sound mind, sound body” philosophy, where she considers what’s going on with her body (sleep deprivation!) and mind (stress!) to help her understand how she’s feeling at any given moment. After all, running throughout pregnancy and postpartum isn’t just about running. Getting enough calories, hydration, mental health, and sleep all matter.

- Recover well

If you track your heart rate variability (HRV), look for any upticks post-workout, a potential sign you’re overdoing it. Don’t track HRV? Pay attention to your sleep and fatigue levels. You never want to be completely exhausted post-workout. “If you're going out for a workout and you have to nap, it probably means your energy system was overtaxed,” Dorrington said.

- Return to running safely

One of the best ways to safely return to exercise after having a baby is to set yourself up for success in the 9 months of training beforehand, Dorrington said. “Women are twice as likely to return to the activities they love, such as running, when they have exercised during pregnancy.”

From there, many people should be able to return to running within 12 weeks postpartum, some sooner, some later, according to research published in the BMJ. Just remember: Motherhood and pregnancy impact every system in the body, and it takes time – months – to find normal again.

After having her daughter, Smith remembers her body feeling “funky” during runs. Sometimes, she wondered if she’d ever feel like her old self again running. She tried to be curious, instead of judgmental, about these feelings. She knew, for example, that she was breastfeeding and not sleeping and that things were supposed to feel different.

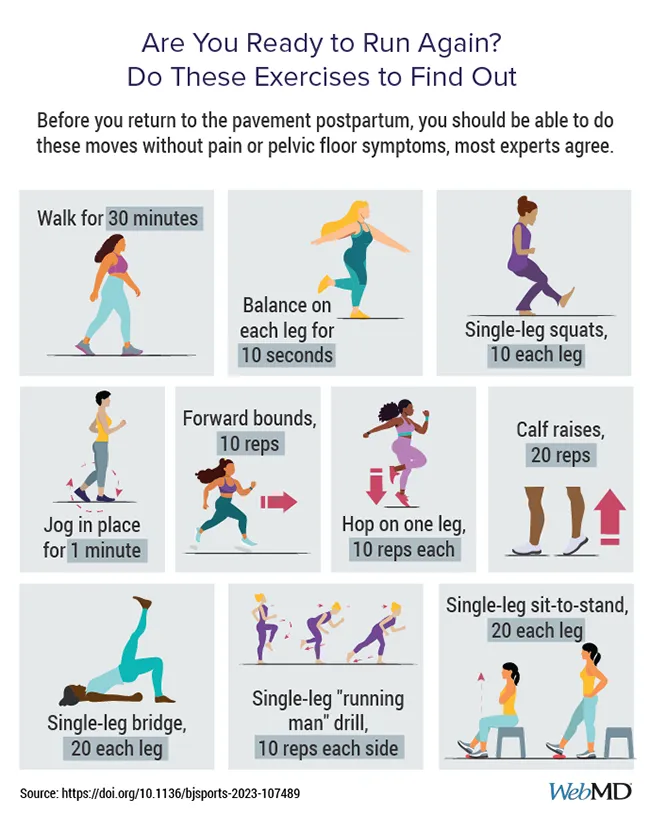

Before you return to running, simple pelvic floor exercises such as Kegels, fully relaxing your pelvic floor, and deep breathing can help get your core and pelvic floor working together. A gradual walk-to-run program can help build back a cardio base.

- Try not to compare

Remember: "Generally speaking, elite athletes aren't breaking records while pregnant,” explained Goodson. For example, Myler’s 9-month mile times appear Herculean feats to a mere mortal, but to her (she can run a 4:42 mile), they were “more like a 10K pace.”

These videos are also only a slice of her reality: “I was doing workouts around a 6-minute [mile] pace my whole pregnancy. It’s not like I ran a 5:17 mile out of nowhere.”

- Make space for the full breadth of your experience

Smith said she’s had many emotions throughout her pregnancy and postpartum experience – and has embraced them all.

“Hands down, pregnancy is the most amazing thing my body has ever done,” she said. “I have such deep gratitude, respect, and appreciation that my body grew an entire human.”

At the same time, she missed being able to push her body at pre-pregnancy levels.

“I really think there's space for feeling both of those things – the sadness of not being able to pursue your passion and perform at the level you're used to, and also the sense of gratitude for what your body is doing.”